Over the next six weeks, 969 million voters will be eligible to cast their ballots in the Indian election — the largest democratic exercise in history.

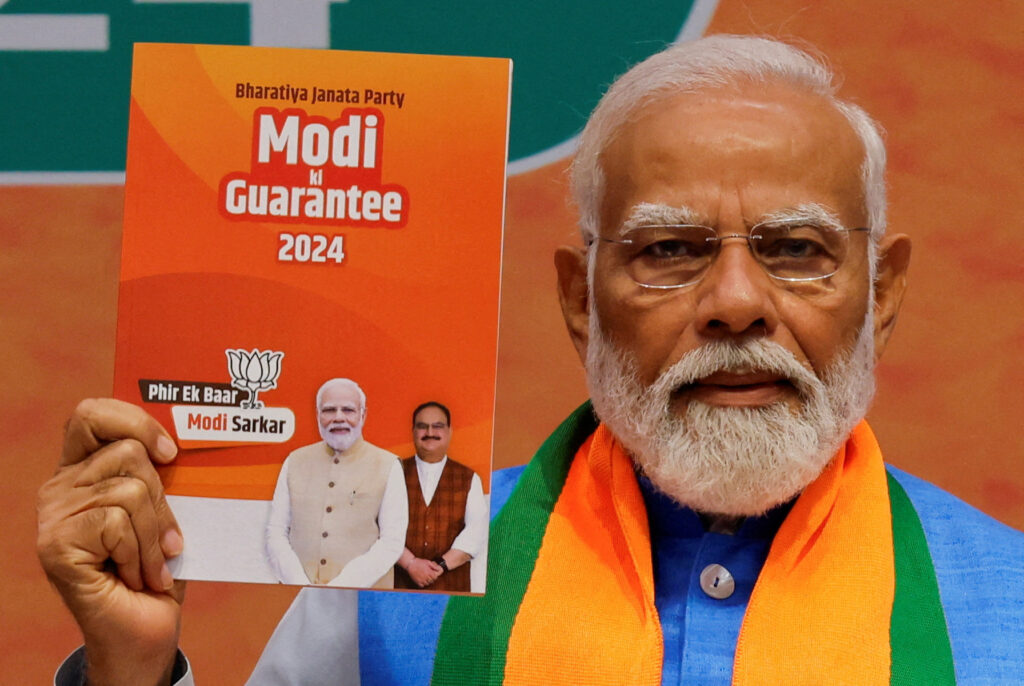

Incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to lead his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to a thumping third successive victory on the back of his personal popularity, economic record and muscular brand of Hindutva politics. Although the election result seems a foregone conclusion — so much so that alarm bells are now sounding about Indian democracy — the question of whether India will fulfil its immense economic and geopolitical potential is anything but certain.

In this week’s lead article, excerpted from the new issue of East Asia Forum Quarterly, Ashley Tellis sets out India’s long-held ambitions for great power status.

‘Ever since independence’, Tellis explains, ‘India’s leaders imagined that the country would become a great power’. Over the past decade-and-a-half this national ambition has been pursued more explicitly, with Prime Minister Modi setting his sights on the ambitious targets of a US$30 trillion economy and GDP per capita of US$18,000 by 2047 — securing India’s status as a developed economy 100 years after its independence.

Today, India boasts the world’s fifth-largest GDP and, as the fastest growing major economy, is rapidly climbing the ladder. Underpinning this is the country’s strong demographics. Not only does India have the world’s largest population, 68 per cent of it is made up of working age individuals between 15 and 64 years old. The geopolitical winds are blowing in India’s favour too. As Tellis points out, ‘growing disenchantment with China and the promise of India’s large market and future economic growth’ are steering Western countries closer to New Delhi as a strategic counterweight in Asia, even if relationships have been soured by worries about India’s embrace of ‘sharp power’ tactics to secure its security interests.

The new issue of the Quarterly, ‘India’s sweet spot’, brings together the contributions of leading experts to examine how India could leverage its favourable economic, demographic and geopolitical circumstances to pursue its lofty ambitions.

The Quarterly highlights India’s growing influence in the Asia Pacific and its increasingly important role in the regional balance of power — albeit one still very much subordinate to China. But contributors also detail how India’s current development trajectory has left large swathes of its population stuck in an unproductive agriculture sector and emphasise the need for human and material investment to generate jobs in manufacturing.

The Asian Review pages cover how the complexity of China’s governance affects its dealings with other states, the longevity of the Indo-Pacific idea and how the growth of migration into Japan might affect its national identity.

In his consideration of India’s national outlook, Tellis contends that India’s ‘long-term success will depend fundamentally on its internal economic performance’. Growth averaging 7 per cent per annum over the last decade is a solid record, especially considering the ‘slow growth during the Cold War [which] stymied India’s great power ambitions’, but it is well below China’s double-digit growth in the 2000s.

Right now, the Indian economy is one-fifth the size of China’s. Even if China stopped growing tomorrow and India continued to expand at 7 per cent per year, it would take until the late 2040s for India to catch up. Without reaching a comparable size and carving out a more significant role for itself in the global economy, India will struggle to stamp its authority as a great power in Asia.

Adding those crucial extra percentage points to growth will require a repositioning of India’s economic strategies.

Central to this effort will be increasing the importance of manufacturing. In most developing economies, the sectoral composition of the economy slowly shifts from being dominated by agriculture to manufacturing as unskilled labour is reallocated into more productive uses. But India has leapfrogged the manufacturing stage, with high-end services already contributing the lion’s share of GDP. Indeed, the BJP government has signalled that it intends to focus on a growth model built on capital expenditure and services, eschewing the traditional path of labour-intensive manufacturing-led growth.

But this approach misuses India’s key comparative advantage — its large pool of low-skilled labour. Focusing on high-end services will push the economy forward but it will leave behind the millions of Indians who don’t have the skills to find jobs in these sectors, forcing them to remain in unproductive employment or exit the formal economy altogether. In a worst-case scenario, the much touted demographic dividend could become a demographic disaster. Failing to provide adequate employment opportunities not only squanders the potential for accelerated growth, it poses significant risk to social cohesion due to increased inequality — already a major concern in a country where the top 1 per cent holds more than 40 per cent of wealth.

The other key hurdle is international trade, where India has historically refrained from participating in the kind of economic integration that underpinned the prosperity of the East Asian economies. The government has taken on a protectionist tilt, seeking to build a ‘self-reliant India’ through inward-looking policy approaches that have at various points seen the imposition of restrictions on laptop and tablet imports and exports of wheat and rice.

Though the government has recently negotiated a spree of FTAs, including with Australia, the UAE and the European Free Trade Association, India can best progress its ambitions through drastically changing direction on the WTO and engaging in larger multilateral trade agreements, which provide an opportunity for deeper integration and a leadership role in the region’s economic architecture. One such option is RCEP, membership of which remains open to India.

Neither the BJP nor the Indian National Congress, leader of the opposition INDIA alliance, have tackled these challenges as part of their election commitments. The BJP’s manifesto signals continuity with the government’s current policies whereas the Congress promises a redistribution agenda without the growth reforms necessary for India’s future prosperity.

No matter what the election result, India’s weight in global affairs will continue to rise over the coming decades. There is an achievable pathway for India to realise the grand aspirations of its leaders, and in so doing lift the living standards of more than a billion people.

But whether it chooses to go down that route, or whether future generations will be left to rue the road not taken, is another matter altogether.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.

Leave a Reply