In 2023, Cambodia commenced a new chapter in its political history. The country went through the inevitable motions of elections, enabling a generational transition in government after four decades of rule by the same core elites to their scions. The main suspense of July’s national election concerned when the generational transition it sanctified would take place.

The Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) went to elections campaigning for Hun Sen as prime minister for the seventh legislature, leaving it open as to when during the electoral term his oldest son Manet, endorsed by his father and the Party as future prime minister, would take his place.

But only three days after the election, Hun Sen declared that he would be stepping down as prime minister, handing the position to Manet, and instead assume positions as president of the senate and president of the Supreme Privy Council to the King, while continuing as president of the CPP. The way the transition in premiership was handled signalled continuity over change, with Manet quietly stepping into his father’s shoes. This cautious approach also meant Manet lost the opportunity to campaign to be elected prime minister in his own right.

In August, new ministers, overwhelmingly the sons of previous incumbents, were appointed for 20 out of 28 ministries. The average age of the ministers is now around 49, many are Western-educated PhD holders. Only three are female, which gives the government a conservative aura. To cater to the growing elite, the government swelled its ranks from 641 to 1422 officials.

Incoming ministers generally took a cautious approach, preferring technocratic work with many hands over pompous initiatives and turgid statements. The new government launched the Pentagonal Strategy-Phase 1, aiming to reform state institutions to make them ‘modern, competent, strong, smart and clean’. Some new ministers are flexing their anti-corruption muscles, notably Minister of Interior Sar Sokha removing and reshuffling national police. The ambition to promote integrity and meritocracy is dissonant with the genealogical principle of July’s selection, creating existential tension the new government seeks to surmount by increasing such efforts.

The new government accelerated efforts towards its fundamental ambition: a national gathering under its unchallenged leadership. Defecting civil society actors and academics were rewarded with prominent positions. Some policy-oriented civil society organisations and think tanks found novel opportunities to engage with ministries, eager to ‘get policy right’, by pitching concrete policy suggestions. For advocacy organisations, the established pattern of suspicion and repression prevailed.

In December, the ranks of the CPP Central and Standing Committees were expanded at a party congress to 1312 and 58 members respectively, to accommodate new generation government leaders. Manet was also elected a fifth vice-president. The Party, controlled by senior figures and with Hun Sen remaining as its president, is gaining in importance relative to the government in connection with the generational transition.

The government’s stance towards the dissolved opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) remained unyielding. In March, CNRP leader Kem Sokha was found guilty of treason and sentenced to 27 years of house arrest. In several court cases, CNRP defendants, including its exiled leaders, were sentenced to lengthy prison terms. There were also multiple violent attacks against opposition members and social activists.

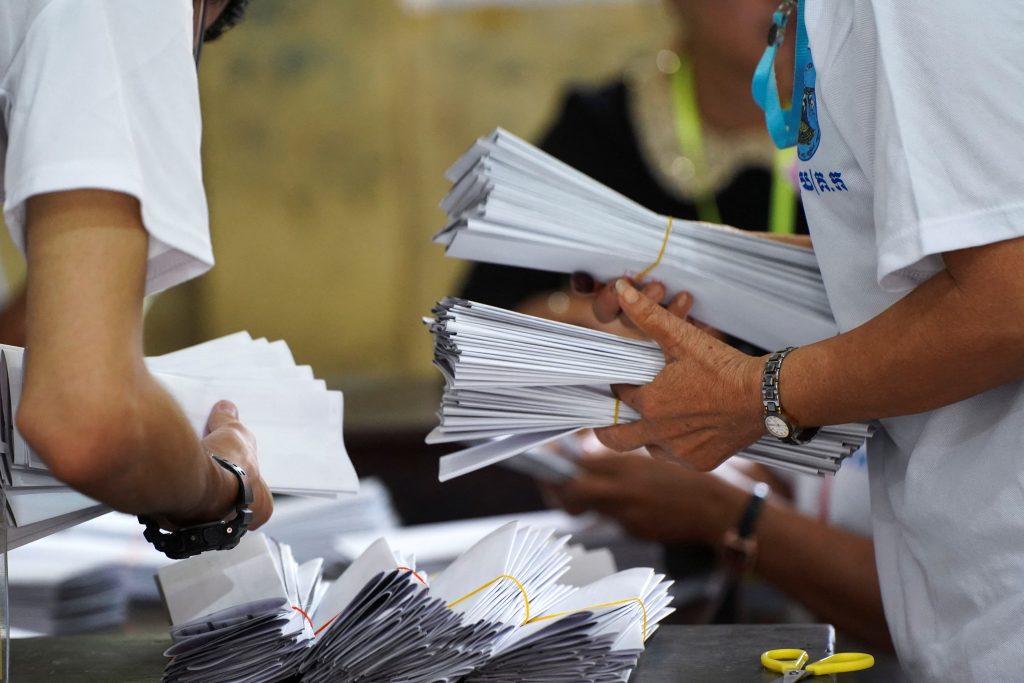

The moderate suspense of the election — whether or not it would introduce a return to competitive authoritarianism — was broken when the Candlelight Party was disqualified from participating over a registration technicality in May. The CPP’s complete possession of the National Assembly was nonetheless interrupted as it won 82.3 per cent of the vote and 120 out of 125 seats. The royalist FUNCINPEC won the remaining five seats with 9.2 per cent of the vote. FUNCINPEC has shown an ambition to move away from its prior identity as a coalition partner to the Cambodian People’s Party and take on an opposition role.

At the end of the year, it had become clear that the Candlelight Party would not be allowed to participate in upcoming Senate elections in February 2024 citing the same technicality, and party leaders urged its commune councillors to vote for its coalition partner, the Khmer Will Party.

Under the administration of US-educated Manet, Cambodia’s relationship with China as its closest political and economic ally remains paramount. At the same time, Cambodia seeks to avoid having to choose between China and the United States.

High-profile mega-projects with Chinese funding during this designated ‘Cambodia–China friendship year’ included the Siem Reap-Angkor International Airport and the forthcoming Funan Decho canal project. Manet’s first official trip abroad after taking office was to Beijing, where he pledged to strengthen ties with China even further. The following week, Manet headed to New York for the UN General Assembly, where he chaired the US–Cambodia Business Forum, inviting US investment.

The United States, European Union and Japan did not recognise the election as democratic and did not send observers — China and Russia did. In the wake of the election, the US State Department announced the withholding of some of its aid but the decision was reversed. This foreshadowed how some Western actors in the new year would increasingly seize the opportunity that the generational transition presents to reboot relations with Cambodia, seen during Manet’s attendance at January’s World Economic Forum and in his visit to France on President Macron’s invitation — replacing initial domestic discretion by internationally produced, boisterous triumph.

Astrid Norén-Nilsson is Senior Lecturer at the Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies, Lund University.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on 2023 in review and the year ahead.