The Indo-Pacific is being transformed by a resurgence of so-called ‘minilateral’ forms of regional cooperation. Whereas state-to-state cooperation was once generally either bilateral or multilateral, minilateral arrangements, typically involving small groups of three to six members, have increasingly come to occupy an in between layer in the region’s security architecture.

The Indo-Pacific region has many examples of minilateralism designed to address joint economic or security issues. While some are confined to narrow objectives, others are broader in their remit, covering diplomatic, security, defence, economic and other types of cooperation. Even then, some minilateral cooperation efforts stand out from the crowd for the strategic critical mass they generate and their potential impact upon the regional order. Such examples can be distinguished as ‘strategic minilaterals’. Minilaterals are increasingly viewed as the ‘way to get things done’ in the region.

Japan and Australia have become deeply engaged in such minilateral endeavours. They have done so both independently and through their own bilateral ‘Special Strategic Partnership’. Rather than simply doubling down on their respective bilateral alliances with the United States or seeking new multilateral arrangements, Japan and Australia have become keen advocates of minilaterialism.

Canberra has pushed hard for the creation of the AUKUS trilateral partnership, designed to knit together three close Anglosphere allies to deliver a nuclear-powered submarine program and expanded defence–technology collaboration. AUKUS has now become a central pillar of Australian strategic and defence policy, even as debates continue to rage about its implementation and formidable costs.

Tokyo has also committed to minilateral cooperation to achieve defence–technology outcomes through its trilateral agreement with the United Kingdom and Italy for the joint production of a sixth-generation stealth fighter under the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP). While not on the scale of AUKUS, the GCAP still represents a major example of high-end minilateral defence–technology cooperation. GCAP costs will run into tens of billions of dollars. The GCAP is the first time Japan has initiated a major defence procurement program outside of the United States.

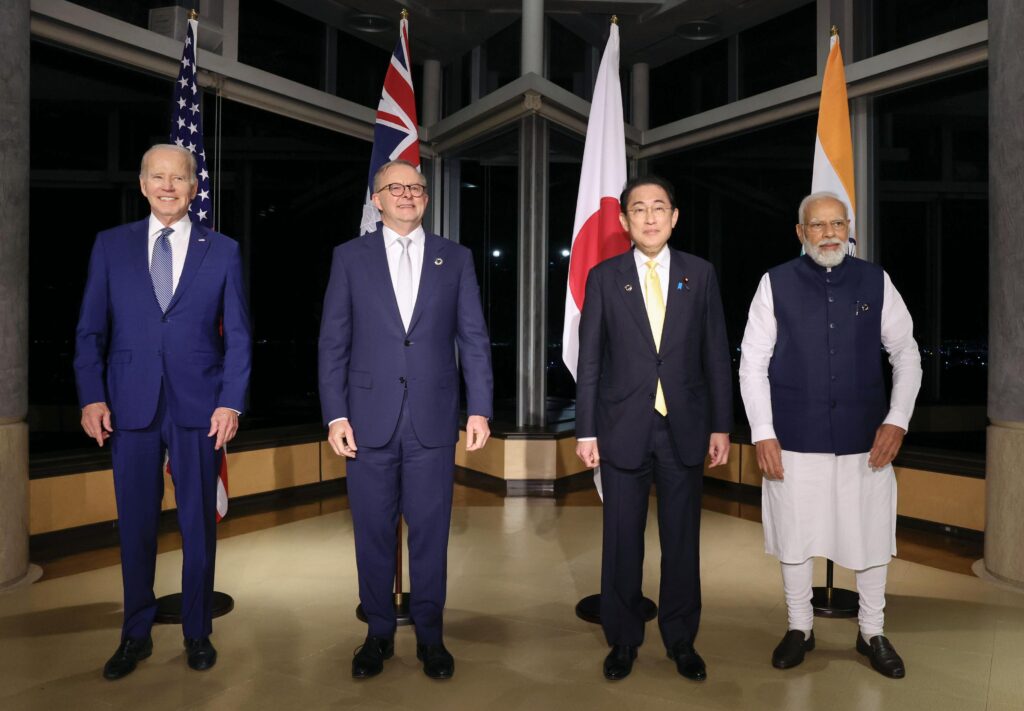

Together, Australia and Japan are members of two other highly significant strategic minilaterals — the Australia–Japan–United States Trilateral Strategic Dialogue (TSD) and the Australia–Japan–United States–India Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad). While AUKUS and GCAP are concentrated on minilateral defence and technology collaboration, the TSD and Quad serve wider strategic purposes.

The TSD was established in 2002 and progressively upgraded in status and accompanying infrastructure. Though inopportunely titled a ‘dialogue’, when the deep linkages between the three parties as core members of the US alliance system are factored in, it is not fantastical to see it as some form of proto alliance. It is increasingly building up an integrated deterrence function among the allies.

The Quad includes the TSD partners with the addition of India, which is not a US treaty ally. This lends the Quad a less cohesive quality, which shows in its hazy proclamations of purpose and less developed formal and informal linkages. The Quad powers have tended to concentrate their efforts on order-building and the provision of public goods to the region. Quad leaders are highly circumspect about any security or defence — let alone deterrence — functions it may serve, though the Quad does show signs of progress in maritime security cooperation through the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness.

It’s notable that bilateral strategic partnerships, such as the Australia–Japan Special Strategic Partnership, are present within several of these minilaterals. This points to the fact that bilateral strategic partnerships play an important role as ‘building blocks’ for these minilateral arrangements.

As US allies, Australia and Japan have used their bilateral partnership to further ‘triangulate’ cooperation through the TSD. They have also sought to use their respective bilateral strategic partnerships with India, along with its membership of the Quad, to bind it closer to the TSD powers. A similar ‘web’ of cooperative arrangements brings in the United Kingdom as well, through AUKUS and GCAP.

All this suggests that strategic minilaterals are highly useful instruments of cooperation. For two middle power states such as Japan and Australia, strategic minilaterals hold significant appeal. They can be easily formed on top of established bilateral cooperation and have the virtue of being relatively informal, flexible and non-binding in comparison with formalised alliances and multilateral organisations. They can quickly act as major force multipliers when joined with a superpower like the United States. Strategic minilaterals also produce a web of additional cooperation, bringing in new partners and furthering links with established ones.

Minilateralism of this kind provides a composite array of tangible benefits across a spectrum of aims, from order-building through defence, technology, economic security and even deterrence. Minilaterals anchored in existing US alliances or strong strategic partnerships with clearly defined aims are likely to be the most effective and durable. This is why AUKUS, GCAP and the TSD hold more concrete potential than the Quad. Since each minilateral serves a different function, together Australia and Japan will continue to pursue webs of cooperation to mitigate the risks of strategic contestation in the Indo-Pacific.

Thomas Wilkins is Associate Professor at the University of Sydney and a Senior Fellow at the Australian Policy Institute (ASPI), as well as non-resident Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Pacific Forum and the Japan Institute for International Affairs (JIIA).

Kyoko Hatakeyama is Professor of International Relations at Graduate School of International Studies and Regional Development, University of Niigata Prefecture.

Miwa Hirono is Professor and Associate Dean in the College of Global Liberal Arts at Ritsumeikan University.

H.D.P. (David) Envall is Fellow and Senior Lecturer at the Department of International Relations at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, The Australian National University, and Adjunct Research Fellow at La Trobe University.

This article was written with the generous support of the Australia–Japan Foundation.

The Indo-Pacific region is experiencing a rise in minilateral cooperation, with Japan and Australia heavily involved in these endeavours to address joint economic or security issues, both independently and through bilateral partnerships. In particular, Australia has pushed for the creation of the AUKUS trilateral partnership for a nuclear-powered submarine program and defence-technology collaboration, while Japan is part of a trilateral agreement with the United Kingdom and Italy for joint production of a stealth fighter under the Global Combat Air Programme. Minilaterals have the potential to provide a host of strategic benefits and mitigate the risks of strategic contestation in the Indo-Pacific.