Western countries’ efforts to enhance their partnerships with India have been embroidered with the rhetoric of a shared commitment to democracy and the ‘rules-based order’ — two things which, it’s implied, distinguish India from China.

How awkward, then, that Asia’s democratic behemoth, the new friend of the ‘rules-based order’, is now caught with a Western liberal democracy in a diplomatic crisis that has uncanny echoes of some countries’ run-ins with Beijing’s wolf-warrior diplomacy, over issues that have a lot to do with clashing views of free speech and the rule of law.

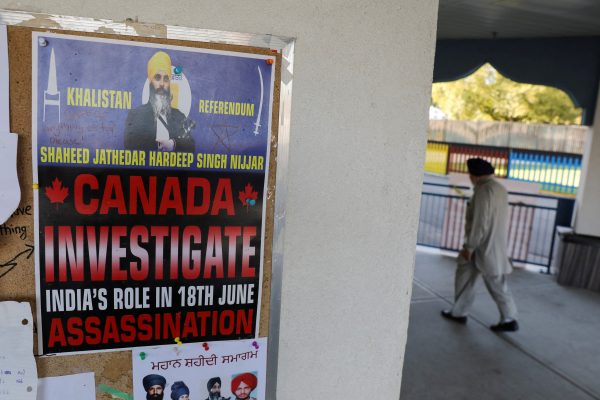

It’s been almost a month since Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told his parliament that Canadian intelligence agencies were looking into credible allegations of Indian state involvement in the murder of a Sikh leader, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, accused by India of involvement in terrorism, in the suburbs of Vancouver.

Much of the discussion of this case has to take place under the cover of the conditional tense, given that a central issue in this affair is that no hard evidence has been made public to back up the Canadian government’s allegations.

This is not to say that Ottawa’s allegations are not true. Trudeau is a political opportunist not exactly renowned for his foreign policy prowess. As his Indian critics emphasise, the Liberal Party he leads has incentives to pander to anti-Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) sentiment in local diaspora communities. But it’s implausible that Trudeau and other high-ranking Canadian officials would recklessly upend the Canada–India relationship — not to mention wedging Five Eyes allies increasingly invested in closer ties with India — on a complete hunch.

Ottawa is clearly confident that India has some case to answer. Whether the killing of Nijjar was in fact an act perpetrated by the Indian state, or rogue elements of it, is another matter.

In the short term, domestic political incentives will see Canada and India stuck in a ‘doom loop’ of diplomatic retaliation, as Kim Nossal argues in this week’s lead article.

The current crisis follows decades of drift and distrust in Canada–India relations, in which the politics of Canada’s resident Indian diaspora have been a central sticking point. As Nossal writes, playing with the identity politics that pervades some migrant communities has been ‘deeply embedded in Canadian political practice’ for decades, with ‘many Indians’ being ‘highly critical of the tolerance enjoyed by Sikh separatists in Canada’ in particular.

For India ‘there is little incentive to back down given that any retreat would merely encourage the continuation of the diaspora politics in Canada that strained the relationship.’ For Canada, issues of sovereignty are now at stake, not to mention the principles of freedom of speech and association, in the face of what US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken implicitly characterised as a possible case of ‘transnational repression’.

The issues go deeper than diplomatic niceties. The language of shared values invoked whenever Western leaders meet their Indian counterparts papers over a clash of systems — not of democracy and authoritarianism per se, but between liberal versus illiberal democracy.

As the historian Tripurdaman Singh observes, authoritarian practices have been ‘structural features’ of India’s political system since independence, despite the vibrancy of its civil society and electoral competition. These heritages, writes Christine Fair, have a fundamental impact on how the Indian state approaches the articulation of ‘separatist’ sentiment.

India has a proper and legitimate interest in not seeing the Indian diaspora become a base for supporting violent political movements. By reassuring New Delhi that this interest is taken seriously, Western governments will be in a stronger position to push back against any Indian efforts to police diaspora communities’ peaceful exercise of their political rights abroad, regardless of their alignment with the BJP’s domestic political agenda.

This will involve engaging in good faith with Indian authorities when they present evidence of terrorist activity in the diaspora, while recognising that India’s legal institutions are not corruption-free and, and its terrorism laws are highly amenable to being abused to repress nonviolent activism.

‘While India needs to understand how its shambolic justice system at home influences the way its claims about terrorists abroad are assessed’, Fair argues, ‘Western leaders need to acquaint themselves with important aspects of Indian history — such as the Khalistan militancy — that contextualize [Indian] concerns.’

Such India literacy among the political classes of countries with large Indian diasporas, such as Canada and Australia, will allow politicians and the media to engage with those communities without being drawn into local fronts in India’s domestic political fights in ways that both undermine cohesion at home and impact important government-to-government relations.

Sensitivity to Indian perceptions of double standards will also be valuable. Western governments should keep in mind the legacies of their own complicity in the dark underbelly of the US-led War on Terror, which involved torture, extrajudicial killing on foreign soil and arbitrary detention — not to mention the calamitous invasion and occupation of Iraq.

When many in India and elsewhere across the Global South view the rhetoric around the ‘rules based order’ with cynicism, this is the kind of thing they have in mind.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.

Indian constitution does not allow any part of it freedom to secede. US too does not allow and went through a long civil war once. There is no automatic or fundamental justification for right to secede, as the people who claim to be aggrieved and want to secede, almost always, do not show any allowance for freedom within their claimed area to other minorities.

The article is excellent and brings to forth the contradictions in Western claims of rule of law and their own behaviour at several times in history.

Making an assumption of India’s guilt just because Trudeau claimed in Canadian parliament is an overreach and cannot be an assumption.