The challenge for the US and Western allies, as well as to the regional actors, is to find an appropriate political strategy to address those causes and conditions on an enduring basis. At present, no such strategy exists.

When al-Qaeda executed its September 11 terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush declared a ‘war on terror’. The specific goal was not only eliminating al-Qaeda and its supporters but also marginalising the forces of radical political Islam in world politics. Fourteen years later, despite the strategic changes enacted by President Barack Obama, al-Qaeda has survived. The group continues to have operational capability from Pakistan to Iraq to Yemen and Libya and new like-minded extremist groups, including Boko Haram and al-Shabaab, have grown to cause havoc in the Horn of Africa, North Africa as well as the African hinterland.

The problem with the war on terror approach was that it placed too much primacy on the use of brute force without a comprehensive political strategy — involving modification in Western policy priorities — to address the causes of extremism. Little or no effort was made to prompt authoritarian regimes to pursue structural reforms in support of empowering the people of the Muslim Middle East to have a determining role in charting the destiny of their countries and to free themselves from outside hegemonic interferences.

Israel was not pressured enough to abandon its colonial settler occupation of the Palestinian lands, including most importantly East Jerusalem, Islam’s third holy city after Mecca and Medina. No effective plan was unfolded as to how to bring peace, stability and democracy after the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, which — in the process of overthrowing Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship — also dismantled the Iraqi state. The same has largely proved to be the case with the US-led intervention in Afghanistan.

The US and its allies found it expedient to put their self-interests ahead of the consistent support that they should have given to the ‘Arab Spring’, now a winter of despair and soul searching for all its pro-democracy instigators. They were quickly prepared either to back or conspicuously consent to a counter-revolution by the old authoritarian regimes in the region. And they remained content with a ‘do nothing’ policy in the hope that somehow the Syrian crisis would sort itself out against the Iranian-backed and Russian protected Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorship. It is no wonder that in this context there is a global expansion rather than a reduction in the number of extremist groups across the Middle East and beyond.

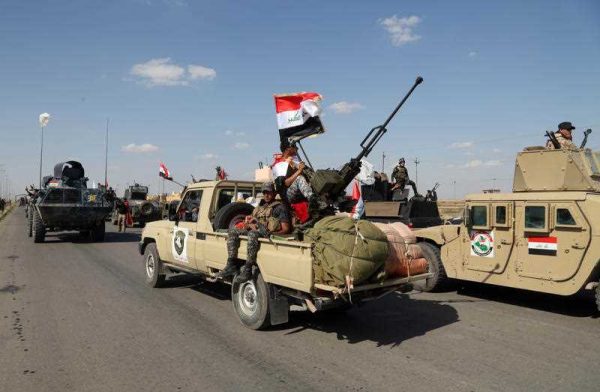

Today, extremism — embodied most prominently in horrifying actions of IS — carries the threat of a violent jihadi and counter-jihadi struggle dominating world politics. IS has been countered not only by the US, its allies and the Islamic Republic of Iran, America’s long-standing regional adversary but also by private citizens around the world who have travelled to war-torn Syria and Iraq either to fight for IS or the opposing forces.

Western countries complain about their Muslim citizens being misguidedly radicalised in support of IS, but they have fallen short of preventing some of their other citizens from taking up the counter-jihadi causes and dying in Iraq and Syria. Equally, they have hardly acted vigorously or prudently to assuage the concerns of many of the 1.5 billion Muslims in the world being targeted, raising the spectre of Islamophobia amongst them. Much of the rhetoric claims a higher moral ground that conveniently forgets the West’s misdeeds in Abu Ghraib, Bagram airbase, and Guantanamo Bay, or even the violence of French colonialism in Algeria.

The West should draw not only on the horrendous actions of Muslim extremist groups, IS in particular, to justify their anti-violent Jihadi responses, but also should go beyond this by looking at whether their own strategy has been partly responsible for what has transpired as an ‘Islamic threat’.

If the real wish is to remove the threat of Muslim extremism, the US and its allies need to engage in policy actions that focus on addressing the long-term structural conditions that allow Muslim extremist groups to thrive in the first place.

Amin Saikal is Distinguished Professor of Political Science, Public Policy Fellow and Director of the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies (the Middle East and Central Asia), and author of Iran at the Crossroads, London: Polity Press, 2015 (forthcoming).