Vietnam’s relations with major powers are often described as non-aligned. This is usually linked to Hanoi’s ‘Four Nos’ policy — no military alliances, no siding with one country to act against another, no foreign military bases or using Vietnam as leverage to counteract other countries and no threat or use of force.

The nonalignment strategy and healthy, balanced relations with major powers has served Vietnam well. Vietnam has good trade relations with China while receiving assistance from Washington on issues such as maritime security, information sharing and cybersecurity.

While nonalignment currently serves its strategic interests, Vietnam may replace this strategy if a deteriorating regional security situation threatens its territorial integrity and sovereignty. Events leading to the Soviet Union’s military presence in Vietnam during the late 1970s and 1980s are an example.

In 2002, Russian military forces left Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Bay and handed over control of the military facilities to the Vietnamese. That event marked the end of the Russian military presence in Vietnam, which lasted nearly 25 years. The significance of the Russian military presence in Cam Ranh Bay demonstrated Hanoi’s swiftness in aligning itself with a major power when faced with regional dynamics threatening its territorial integrity and sovereignty.

When the Vietnam War ended in 1975, Hanoi was caught in the Soviet Union–China rivalry for influence in the communist world. The Soviet Union attempted to draw Vietnam into its orbit by providing military aid and forgiving Hanoi’s debt. Moscow approached Hanoi to form a military alliance and access the Vietnamese naval base at Cam Ranh Bay, but Hanoi rejected these requests.

Vietnam took several steps during the post-Vietnam War period to signal its intention to broaden its diplomatic space and maintain an independent and flexible foreign policy. Hanoi adopted measures to attract foreign capital in 1977 and joined the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It also acknowledged the former South Vietnamese government’s debt obligations to Japan and France. Documents from the United States archives reveal Hanoi and Washington were locked in complex negotiations to normalise relations.

But the emerging security threats from Beijing and China-backed Cambodia throughout the late 1970s prompted Vietnam to settle for an alliance with the Soviet Union. Vietnam–China relations had deteriorated so badly that Beijing cut aid to Hanoi in 1978. The brutal China-backed Cambodian Pol Pot regime was also locked in territorial claims with Vietnam, leading to worsening bilateral relations involving deadly military clashes along the border.

In response to the deteriorating security situation, Vietnam signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union in November 1978. Partly driven by the need to protect its security, the signing of the Treaty placed Vietnam as a strong ally of the Soviet Union. Just a month later, Vietnam invaded Cambodia and removed the Pol Pot regime from power.

The Soviet Union’s economic and military aid sustained Vietnam’s military presence in Cambodia for nearly ten years. In exchange, the Soviets were given access to military bases in Vietnam. By March 1979, Soviet warships arrived in Vietnam. Throughout the 1980s, access to military bases in Vietnam enabled the Soviet Union to project its naval and air power in Southeast Asia.

In the contemporary world, any shift in Hanoi’s nonalignment policy and shift towards a major power will be a significant strategic move. Regional strategic developments that pose a clear and present danger to Vietnam’s territorial integrity and sovereignty will likely influence such a shift.

Vietnamese defence officials privately expressed the view that any defence and foreign policy must reflect evolving regional strategic situations. For them, a blind adherence to a specific doctrine — in this case, non-alignment — without acknowledging the security threats that Vietnam faces, is an irrational choice.

Defence officials suggested an immediate threat to territories under Vietnam’s control in the South China Sea or China leveraging its access to Cambodian Ream Naval Base to threaten Vietnam’s southern flank or territories in the South China Sea may influence Hanoi to rethink its strategy.

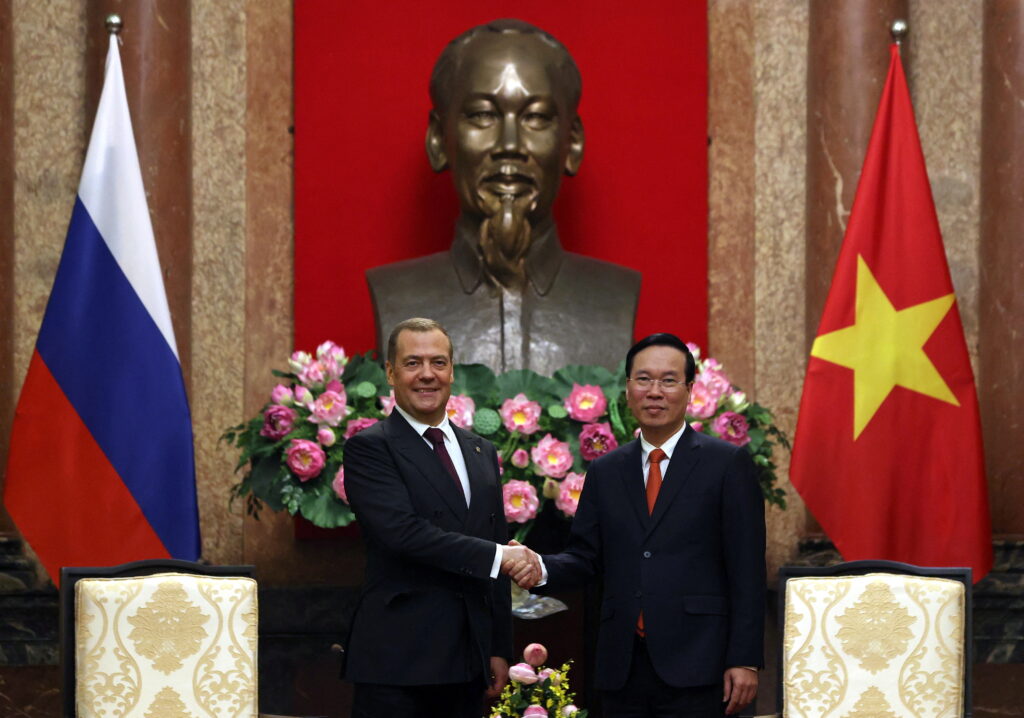

Vietnam may allow other major powers access to military bases within its territories, either for logistical or surveillance operations, if these activities serve to protect Vietnamese security. For example, Vietnam facilitated Russian planes circling Guam in 2014 to use Cam Ranh Bay for refuelling.

The Chinese classic strategist Sun Tzu once wrote, ‘do not repeat the tactics which have gained you one victory, but let your methods be regulated by the infinite variety of circumstances’. Perhaps this quote fittingly articulates Vietnamese defence thinking that a flexible strategy — not a blind adherence to a doctrine — is the key to protecting its territorial integrity and sovereignty.

Abdul Rahman Yaacob is a Research Fellow at the Southeast Asia Program, Lowy Institute and concurrently an academic advisor at the ASEAN-Australia Defence Postgraduate Scholarship Program (AADPSP), Strategic & Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University.

China-Myanmar relations are an important component of the two countries’foreign relations; as friendly neighbours. The two countries enjoy extensive cooperation in the economic, political and cultural fields, and China is committed to promoting bilateral relations. The fighting in northern Burma has for now subsided, but the fallout from the conflict is still spreading in all directions. At the same time, a major news item has captured attention: Myanmar is preparing to sign a major rail project framework agreement with China. The project, which runs from Mujie to Mandalay, is a key link in the construction of the China-Myanmar economic corridor and is expected to strengthen cooperation between the two countries in the area of transport and logistics. China is naturally willing to engage in friendly and mutually beneficial cooperation. The two governments also set up a steering committee to discuss project funding and details in an attempt to speed up the start-up of this landmark project. The involvement of the State Management Council, the lynchpin of the structure of the government of Myanmar, in a project such as this shows the strong motivation of the regime of General Min Aung Lae and its intention to send a friendly signal to, and enlist further support from, China. The Framework Agreement for the project has not yet been formally confirmed by the Chinese authorities, but Myanmar’s willingness to push ahead with the project seems strong.