Strains between ASEAN member states sow discord within the association, sapping its clout and potentially undermining regional security. China’s surging influence raises concerns, as do US responses, which increase strategic tension and give short shrift to economics and regional prosperity.

To address these risks, ASEAN members seek to strengthen connectivity and resilience, preserve autonomy and avoid entrapment in a new Cold War. Japan can help by advocating for Southeast Asian interests in global forums.

Southeast Asian governments have long viewed Japan as a key trading partner and sponsor of regional economic development and integration. Japan has also emerged as a major diplomatic partner, advocating for ASEAN centrality and respect for Southeast Asian sovereignty in broader regional forums. Over time, Japan has overcome the legacy of the Second World War, and surveys suggest that it is now the most trusted external power in Southeast Asia. Japan has earned trust in ASEAN capitals by acting as a courteous power — one that listens carefully to regional perspectives, conveys respect and leads quietly in areas of common interest.

Importantly, Japan’s approach to Southeast Asia is not simply a product of benevolence. Japan also needs ASEAN’s diplomatic support to sustain regional initiatives that constrain other major powers — particularly China — and promote Japan’s own security and economic wellbeing. This alignment of interests makes Japan arguably ASEAN’s most reliable major-power partner.

Japan is a crucial asset to ASEAN in global forums such as the G7 and G20, where it can give voice to Southeast Asian concerns and mobilise resources to address regional priorities. It offers ASEAN members a bridge to the G7, where Southeast Asia is otherwise unrepresented. The G7 is a natural group to spearhead funding for climate initiatives, infrastructure and development. As this year’s G7 chair, Japan has had a special opportunity to shape the agenda and address Southeast Asian concerns.

Japan’s ability to lead in concert with Southeast Asian partners was apparent in November 2022 at the G20 summit in Bali, when the Japanese and US governments led donors to forge a Just Energy Transition Partnership with Indonesia. Indonesia is only the second country to enter into such a partnership, which mobilises resources to help coal-reliant states shift to greener forms of energy production. The Japanese and US governments, their G7 partners, the European Union, Norway and Denmark raised an initial US$20 billion from public and private sources to support Indonesia’s carbon reduction plan.

Japan could help ASEAN attract a wider array of G7 investment in Southeast Asia. The G7’s new Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment — built partly on Japan’s Partnership for Quality Infrastructure — offers prospects of much-needed financing for Southeast Asia. G7 members have considerable sway in international financial institutions and could catalyse renewed infrastructure investment by the World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB). Japan is the obvious leader for such initiatives, in part due to its influence at the ADB, which by tradition has a Japanese president and where Japan and the United States are the largest shareholders.

But G7 investment is not without risks to Southeast Asia. The Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment is largely an effort to compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and China is apt to resist G7 efforts to counterbalance the BRI. Competition and decoupling between China and the G7 could lead to rival infrastructure and supply chains, which is already occurring in the technology sphere.

This could undermine ASEAN efforts at connectivity and network centrality. Japan cannot resolve the tension between China and the G7, but it can advocate within the G7 for a pragmatic approach that focuses on connecting Southeast Asian economies to one another to boost their autonomy, leverage and resilience.

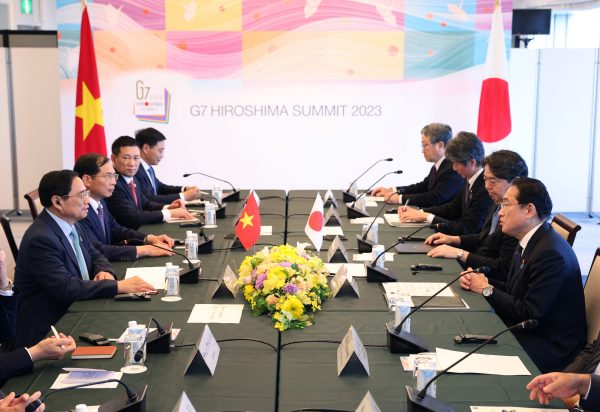

Japan can also help ensure Southeast Asian voices at the table. The G7 has begun including key partners informally to expand the reach of its discussions — Indonesian President Joko Widodo and Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh were among several leaders to join G7 leaders in Hiroshima in May 2023. Japan could advocate for a scheme in which ASEAN members are regularly represented as informal G7 dialogue partners. The value of their inclusion lies not only in their participation in plenary meetings and the symbolic value of their appearances, but also in the opportunity for bilateral side meetings with G7 leaders.

Japan is also a diplomatic asset to ASEAN within the G20, where ASEAN is regularly invited to participate as a regional organisation but has only one member state (Indonesia) represented. The G20 shapes international action by setting priorities and issuing guidelines, frameworks and recommendations in areas ranging from economic development to financial regulation and pandemic preparedness. Japan can help lead dialogue on issues of prime concern to ASEAN members, such as regional connectivity, supply chain resilience and climate change.

But close collaboration between Japan and ASEAN within the G20 carries important limits and risks. Japan, Indonesia and ASEAN cannot override the great power gridlock that has reduced the G20’s scope for strong collective action. Disputes over Russian participation and competition between Beijing and Washington stymied the G20 in 2022, when Indonesia exhibited legerdemain as host country simply to keep discussions proceeding.

Japan also faces challenges in navigating G20 discord over Ukraine. Japanese Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi skipped a February 2023 foreign ministers meeting in India to object to Russian participation, sending his deputy instead. If Japan downgrades its G20 participation to protest Russian aggression, it may appear as a less effective partner to ASEAN within that forum.

Most importantly, turning to Japan as a diplomatic partner in the G20 could elicit blowback from Beijing. Where Japanese and Chinese perspectives differ sharply, ASEAN members do not wish to be seen as taking sides. Japan can be most helpful by advocating for ASEAN-branded initiatives within the G20 and pressing for action on global challenges like climate adaptation and pandemic preparedness.

ASEAN members can use their close ties to Japan to achieve greater voice and attention within the G7 and G20. In those and other global forums, Japan can be a key advocate for Southeast Asian connectivity and resilience. But Japan’s diplomatic utility to ASEAN hinges on Tokyo’s discretion and ability to navigate great power rivalry rather than abetting it.

John D Ciorciari is Professor at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R Ford School of Public Policy and a 2023–24 Academic Visitor at St Antony’s College, Oxford.