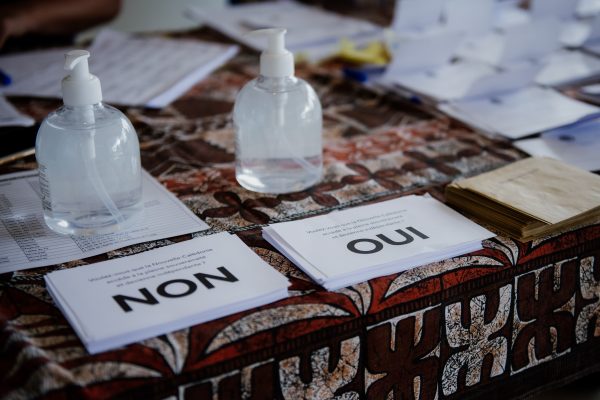

Macron dismissed the low turnout of 43.9 per cent as legally insignificant, despite this being only just over half of the 85.6 per cent who cast ballots in the previous independence referendum in October 2020. Appeals by the pro-independence Front de Liberation Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS) to delay the poll due to the debilitating impact of COVID-19 on Kanak communities fell on deaf ears. Pro-independence parties therefore refused to participate, leaving the polling booths in majority-Kanak districts empty.

The staunchly anti-independence parties in New Caledonia have preferred to speedily conclude the three ballots anticipated under the 1998 Noumea Accord. They feared that any delay might play into the hands of the independentists. Paris wanted to complete the cycle of referendums ahead of the April 2022 presidential election, but in the process the quest for a consensus outcome has been abandoned.

The close alignment between Paris and New Caledonia’s loyalists has ended the traditional portrayal of France’s role as that of a neutral umpire in the domestic squabbles of its imperial outpost. In 1988, Michel Rocard’s government negotiated a peace deal to end the violent inter-communal conflicts of the 1980s. The Matignon-Oudinot Accords promised a referendum a decade later, offered affirmative action for disadvantaged Kanak communities and established provincial administrations covering the majority indigenous North and Loyalty Islands regions.

When the envisaged poll fell due in 1998, both sides negotiated a follow-up deal, the Noumea Accord. This pushed the date for an independence referendum back by 15–20 years and initiated a power-sharing arrangement under which pro- and anti-independence politicians were to collaborate in a collegial government.

Under the Noumea Accord, various executive powers have been steadily devolved from Paris to Noumea. The final decision on whether to transfer the remaining ‘regalian powers’ — including defence, foreign affairs and justice — hinged on the cycle of three referendums that took place over 2018–2021.

Although the decision to hold the third referendum was made by New Caledonia’s territorial assembly, the French government unilaterally set the 12th December referendum date. The Noumea Accord provides that only the support of one third of the 54-member Congress was required for a final poll to go ahead. In formal legal terms, Paris may have acted within its statutory powers in setting the date, but this entailed a hasty schedule with the third referendum taking place only 14 months after the second.

Until recently, time seemed to be on the side of the independentists. The ‘no’ vote declined from 56.7 per cent in 2018 to 53.3 per cent in 2020. By agreement, the franchise has been restricted to those who arrived before 1994, much to the consternation of the loyalist parties. More young Kanak voters have come of age, while in net terms around 2000 New Caledonians have been departing the territory each year, mostly non-indigenous.

The FLNKS’s strategy has been to forge alliances with other communities, so-called ‘victims of history’, including settlers who were brought to the territory under French rule. That approach has seemed to be paying off. In February, a party representing the descendants of migrants from the islands of Wallis and Futuna, around 8.3 per cent of the population, switched sides to back the election of the territory’s first Kanak president.

The abandonment of the 33-year-old path of seeking at least a partial consensus in managing New Caledonia’s affairs responds primarily to developments in mainland France. In 2022, Macron faces presidential and legislative elections with the main threat coming from right-wing parties who have close ties with New Caledonia’s loyalists.

With the referendum concluded, New Caledonia’s anti-independence parties now want to press their advantage by ending restrictions on the franchise, which also apply to provincial elections, and by halting the ‘re-balancing’ programs that give a disproportionate share of local government expenditure to majority-indigenous provinces.

The Noumea Accord’s limits on the franchise may contradict Gaullist traditions of ‘equal citizenship’ and the ‘one and indivisible republic’, but they were a critical part of the deal. Its signatories recognised that New Caledonia’s population had been unfairly swollen in the 1970s and 1980s by the arrival of thousands of settlers from the mainland, many of whom still circulate to-and-fro on short-term contracts.

Like New Caledonia’s anti-independence parties, President Macron and his Minister for Overseas Territories Sebastien Lecornu now say that the Noumea Accord era is over and that the time has arrived to establish a new statute. Yet the Noumea Accord provides that, whatever the outcome of the third referendum, ‘the political organization established by the 1998 agreement will remain in force, at its last stage of development, without the possibility of going back, this “irreversibility” being constitutionally guaranteed’.

New Caledonia therefore still has an institutional apparatus founded upon a constitutionalised compact between two communities — which rests on the search for compromise — but now with a referendum outcome that entailed a breach with the quest for a mutually agreed political settlement.

In the long term, then, Paris may have shot itself in the foot. Owing to insistence on a non-consensual referendum without Kanak participation, the moral authority of the future will lie with those who seek a further but fairer contest, with the involvement of all communities.

Jon Fraenkel is Professor of Comparative Politics at Victoria University of Wellington.

He is indebted to Denise Fisher and Adrian Muckle for comments on an earlier draft.