on offer in the so-called ‘Beijing consensus’. It is precisely this reality, and the hitherto impressive performance of the Chinese economy, that has led some to conclude that, as Martin Jacques puts it, China will ultimately ‘rule the world’.

Of course, Chinese hegemony is not unprecedented. For hundreds if not thousands of years, China exercised a form of hegemonic influence over its region in relative isolation from outside powers. The tribute system, in which neighbours of China ritualistically acknowledged Chinese dominance, was necessarily a comparatively local affair in an era before international integration. US hegemony, by contrast, has been increasingly global, a reality that has been entrenched by technological innovation and its own Cold War triumph. If China is ever to match or eclipse the United States as the dominant power, it will also have to exercise power on a hitherto unprecedented scale and scope.

The first obstacle to any hegemonic ambitions that China may harbour is institutional. There is a certain inertia in international affairs that makes institutions hard to change or remove, even when it is evident that they no longer serve the purpose they once did. Institutions such as the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO have endured at least in part because many people wanted them to, especially in the absence of real or effective alternatives.

China is beginning to develop a rival or parallel set of international institutions Such as the Shanghai Co-operation Organization and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). China’s efforts have clear, if largely unacknowledged, parallels with the US’s highly successful Marshall Plan.

Is this, therefore, an unambiguous manifestation of China’s increased influence and growing hegemonic power? Up to a point, it is. Clearly, China’s economic weight means that it is already too important to gratuitously snub or offend. And yet, it is also obvious that some countries are taking an entirely instrumental and pragmatic attitude toward China: they may not like it terribly much, but they still recognise the importance of maintaining good relations.

This highlights two glaring weaknesses of China’s hegemonic challenge that are unlikely to be easily overcome. First, China has no friends. True, there is always North Korea. But as the saying goes: with friends like that, who needs enemies? The reality for China is that its quasi-allies such as North Korea, Pakistan, Laos and Cambodia, are weak, unreliable and opportunistic.

By contrast, the United States has a series of bilateral security alliances that have endured long after the Cold War ended. In East Asia in particular, alliances with Japan and South Korea have proved durable and, from a Chinese perspective, too close for comfort. Allies such as Australia have been willing to fight for the United States in conflicts with little bearing on their own security. China has no such friends or allies.

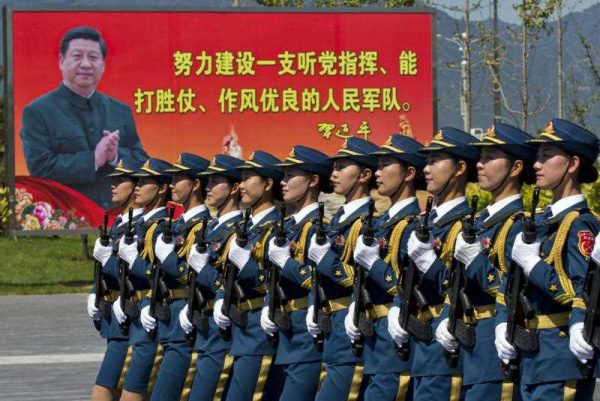

Recent Chinese strategic and foreign policy moves mean that this relative isolation is unlikely to change any time soon. On the contrary, China has alarmed its perennially nervous neighbours in much of Southeast Asia with its assertive, even aggressive, territorial ambitions in the South China Sea. The United States was not the only beneficiary of the open international economic order it led, even if it benefited from it more than most. By contrast, the predominantly national — and increasingly nationalistic — focus of Chinese policy is what strikes many observers most these days.

Hegemony can be achieved by persuasion or coercion. While there is no doubt that the US has done a good deal of the latter at times — including in East Asia — part of the reason its influence has endured is because it has enjoyed the freely given support of other states. Equally important, if rather more difficult to quantify, the US has undoubtedly benefited from a form of ‘soft power’ that has reduced the transaction costs associated with maintaining international primacy. At this stage, China has no such attributes.

Despite a good deal of talk within China about the unfairness of the existing order, historically it has taken few concrete steps to present an alternative vision — which is what makes the AIIB so interesting and potentially significant. But even if the AIIB proves to be successful as a way to underpin massive investment in the region, there will still be significant constraints on Chinese influence. Not only has China promised to abide by essentially Western standards of good governance and transparency in the way the AIIB operates, it will be difficult for China to use its economic weight unilaterally.

As China faces the prospect of its first full-blown crisis of capitalism, the fate of more than its economy is at stake. China’s rather brittle-looking authoritarian regime has staked its reputation and legitimacy on its capacity to deliver continuing economic development. Unless it can continue to do so and simultaneously manage the internal contradictions of inequality and instability that are endemic to capitalism, debates about its possible hegemonic influence and the viability of a Chinese alternative model of development will not even be of academic interest.

Mark Beeson is Professor of International Politics, Political Science and International Relations at the University of Western Australia.

An extended version of this article originally appeared at Global Asia.

It is the easiest said and the hardest done. China could boast its preeminence for over two thousand years in isolation and with dwarfs as its neighbours.

This has changed drastically. There was no time like this in Chinese history when she was so dependent as she is now upon the outside world.

Today China has hardly anything constructive to offer its neighbours and the world or anything to help solve the common problems that face the world.

If China wants to be respected as Tang or Song China was, it has got to ask not what the world can do for it but what it can do for the world.

“China has no friends.” China has the only friend worth having: Russia – bigger, tougher, meaner and smarter than anyone else.

And “China’s rather brittle-looking authoritarian regime has staked its reputation and legitimacy on its capacity to deliver continuing economic development” is nonsensical either way you look at it.

The Chinese government’s legitimacy is based on its Confucian virtue, as all Chinese governments have been since Jesus was born. The Chinese people would not tolerate it otherwise. And the cynical Chinese give it high approval, according to Harvard and Pew. According to a recent World Values Survey, 96 percent of Chinese expressed confidence in their government, compared to only 37 percent of Americans. Likewise, 83 percent of Chinese thought their country is run for all the people, rather than for a few big interest groups, whereas only 36 percent of Americans thought the same of their country. http://www.wvsevsdb.com/wvs/WVSData.jsp?Idioma=I.

Virtue aside, its capacity to deliver continuing economic development is unmatched in human history: 100% wage rises for all Chinese every ten years for 50 years. And 90% home ownership and an average Chinese household net worth that will surpass Americans’ in two years.

China’s governmental legitimacy is doing fine.

China may like to think that Russia is its friend.

But Russia still remembers how it tried to have closer relations with the West, only to watch as the West poured trillions of dollars in investment into China instead, while very little went to Russia.

Russia also remembers how China reverse-engineered Sukhoi’s SU-27 and export it as the J11 without Russia’s permission.

It also remembers how China did not join Russia in vetoing the UN Security Council’s resolution condemning the Crimean referendum.

Russia also remembers how its more loyal friends India and Vietnam are constant targets of PRC threats and intimidation.

Russia is also very much aware that China merely wants to exploit Russia’s current isolation from the West and that Russia need not isolate itself even more by siding with a China that slanderously and contemptuously rejects a PCA Tribunal’s binding ruling.

The Chinese government’s legitimacy was based on the continued economic investments from the West.

After the Tiananmen Square massacres, the PRC offered its people economic progress that only trillions of dollars invested by the West could provide, in return for more time in power.

Today, China’s “New Normal,” “big-but-not-healthy,” debt-ridden economy will not keep its population very happy for too long. And so the Party needs to incite external threats to try and legitimise its grip on power.

And for Beijing, inciting animosity against China is strangely easier done than said.

In thousands years of China history, wars, mostly civil wars, were just normal part of lifestyle. Peace had never lasted long enough for its people on the street to get evolved intellectually. Money and economics were used frequently to manage its surrounding nations when the country was strong and prosperous. War breaks out when internal politics divert attention to an internally weak and unstable ruling.

Currently, China is using its economic might to buy the world into cooperation yet military wise it is unable to extend beyond it’s coastline as countries are less willing to share sensitive facilities with a two-face-giant who never hesitate to threat and limits its information in one-way manner.

In recent years, many more production plants are retreating out of China to nations far west of Asia. While China domestic is growing increasingly in nationalism among the younger generation who had never experienced large-scale war. China’s economic might is also its curse as it can choose to ignore international norms or rulings which are not in its favour. This strikes a similarly shown in its people, acted similarly in civil judgements.

Professor Beeson makes some very good points as to the kinds of obstacles that would prevent China from achieving hegemony in any form whatsoever. However, situations and circumstances do change over time, not least institutional change. The point I wish to make is that “China will never rule the world” because they lack one essential ingredient. As to what this may be, I shall leave it to the readers to ponder.