Structurally, the world has witnessed a tectonic shift in power distribution, from a bipolar to unipolar and possibly multipolar arrangement. While rising powers are reluctant to lead unless this serves their national interests, declining powers are losing the capacity they once had.

There has been a surge of both informal and multilateral networks among political and economic powers to fill the gap of governance. In the wake of the global financial crisis, for example, the G20 leaders’ summit was convened to resolve the crisis. Its scope of discussion has expanded to include not only economic issues but also those relating to energy and climate change.

But these informal groupings are unlikely to become the standard bearer of global governance in the longer term. They tend to gradually lose steam over time, without a firm grounding in shared values and norms that inspire confidence and sustained cooperation. These ad hoc groups are doomed to patchwork governance, at best.

A failure of global governance may well result in a turn to regional governance. The Asia Pacific was once known as an infertile ground for regional institutions and had none. But there has been a sea change in the past two decades, with the emergence of a myriad of regional groupings — the so-called alphabet soup — which form a multilayered regional architecture centred on ASEAN.

These institutions have surely contributed to regional dialogue, promoting conversation and practical cooperation, mainly in financial crisis management and in non-traditional security areas, such as humanitarian assistance, disaster relief exercises and piracy control. But they have failed to address core regional issues, such as territorial disputes, competitive arms build-up, national rivalries, and civil war.

In contrast to member states of other groupings that use their sovereignty for regional cooperation and integration, nations in the Asia Pacific strongly cling to their sovereignty and maximise their national interests. This does not lend itself to regional governance. But two factors — namely, economic interdependence and the transnational nature of threats prevalent in the Asia Pacific — compel us to cooperate. Multilateralism thus matters in the region more than ever.

The concept of human security could be the necessary glue for regional integration. The term ‘human security’ has an Asian pedigree, with human security conceived and introduced to policy debate by Asian intellectuals, such as Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq and Indian economist Amartya Sen.

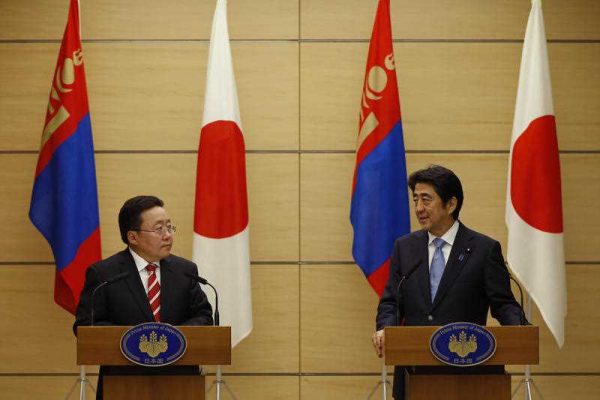

Proponents of the concept originally included Japan and Thailand. Japan defines human security broadly, as ‘freedom from want’, and ‘freedom from fear’. Human security threats therefore encompass a wide range of non-traditional security issues, such as poverty, natural disasters, pandemics, climate change, pollution and terrorism. Human security approaches aim to both protect and empower populations to build their future resilience. Japan embraces human security as a core component of its foreign policy, operationalising it particularly through its development assistance.

Thailand established a Ministry of Social Development and Human Security and was active in supporting the Human Security Network internationally. It was a strong advocate of developing and applying the concept globally, regionally, and domestically. But with the change of government in 2005, Thailand dropped its commitment to human security and no longer uses the concept or the phrase.

Mongolia, on the other hand, introduced human security as a priority policy area in 2000 and has adopted a ‘good governance for human security’ initiative to enhance domestic human security. Today, Japan and Mongolia are the two countries that remain the key promoters of the human security concept in the Asia Pacific.

The region’s strongest opponent to human security was China, who initially criticised the concept as a Western import. But since the SARS incident, China has slowly accommodated the concept, by shifting its focus from the individual to the state. It no longer opposes the intermittent inclusion of the term in regional policy texts.

Human security is now used repeatedly among ASEAN circles. Yet sceptics remain within ASEAN, which prefers to frame threats covered by human security in terms of non-traditional security, a conceptual cousin of human security. Whether the concept is phrased as human security or non-traditional security, the region shares an anxiety over these issues. The region is keenly aware that threats envisioned by these concepts are transnational and demand cooperation.

Human security is no longer simply a mantra. We now need to operationalise the concept, both domestically and in foreign policy, to enable people to live with dignity. For example, international action towards ensuring cyber security and greater cooperation on disaster recovery could help further the primary goals of human security: freedom from want and fear. Human security — or a similar phrase — can help us to understand a potential crisis, and take interconnected, comprehensive rather than piecemeal action. This can eventually create empathy, if not trust, among the players in a region.

What we need today in achieving good governance is to come up with a new label that both acknowledges the blurring of the line between traditional and non-traditional security issues, and can overcome the lack of support in the Asia Pacific for the phrase human security.

Akiko Fukushima is Professor, School of Global Studies and Collaboration, Aoyama Gakuin University, Japan.