Both have fundamentally constrained Japan’s freedom of action in international security and limited Japan’s foreign policy options to those of a middle power. This diplomatic style allowed Japan to focus on post-war economic recovery, which eventually proved to be the key to the nation’s rise as an economic power. But even as Japan achieved economic strength it maintained a restrained posture in dealing with political and security issues, and concentrated instead on cultivating economic and cultural relations with Asia and the world.

Japan’s economic input to the modernisation programs of the Park Chung-hee regime from the mid-1960s was significant in South Korea’s eventual economic success. Japan’s official development assistance and foreign direct investment in Southeast Asia helped to accelerate the economic integration of the region. And Japan’s full-scale support for the ambitious open-door and reform policies of Deng Xiaoping from the end of the 1970s was not insignificant in the eventual rise of China. In short, Japan played a critical role in constructing the foundations of the Asian century.

But these good old days for Japan are now clearly over. South Korea has caught up with or even passed Japan in some economic and cultural dimensions, and Southeast Asia is forming its own political, economic and cultural communities. The impact of the rise of China now goes beyond the region and extends into various corners of the globe. As a result, Japan is searching for a new mission and a new role in Asian diplomacy.

Some say that value-oriented diplomacy is the answer. In recent years, however, this has lacked a coherent theme that resonates across Asia. This was the product of a unique combination of two different considerations.

The first aspect dates back to the end of the Cold War, when the Japanese government started searching for a new rationale for the US-Japan alliance in the absence of the Soviet Union as a major threat. Protecting and promoting universal values was the answer. The main focus of this new foreign-policy orientation was global rather than regional. This has been sustained by central policymakers and bureaucrats who believe that Japan is or should be a global actor.

The second thread of value diplomacy originates from the mid-1990s when Taiwan embarked upon democratisation under the strong leadership of Lee Deng-hui, whom China attempted to intimidate with a series of military exercises. From this time on, anti-China conservative politicians and opinion-makers in Japan began emphasising democracy in their foreign policies. Their perspective is informed by somewhat naïve pro-Taipei and anti-Beijing sentiments.

Universal values like democracy and respect for human rights are, of course, very important in and perhaps even central to promoting peace and stability in the Asian century. But, while Japan might have been right during the Cold War to assert that economic development should precede political democratisation in Asia, the critical question in the Asian century is how universal values will fit into the new Asian context.

The concept of middle-power cooperation might provide a clue. Japan must recognise that it will be a truly equal partner with other Asian countries in the Asian century. Equality in its partnership with ASEAN, for instance, was a key component of Japanese–Southeast Asian diplomacy even in the 1970s. Today, it should be even more obvious that Japan is on an equal footing with many of its Asian neighbours.

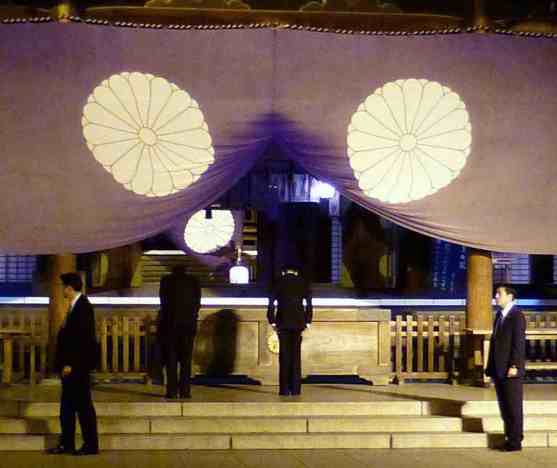

More importantly for Japan’s middle-power, value-oriented diplomacy, it must maintain and cultivate various channels of communication with Chinese civil society. But the current administration of Japan, led by Shinzō Abe, inclines toward containing China by means of ‘alliances of democracies’, which in essence could be called the ‘geopolitical use of values’. This encourages an unhealthy preoccupation with China and breeds regressive attitudes towards the history problem among some important members of the government, while anti-Japan sentiments in China run deep. Thus, China and Japan seem trapped in an emotionally charged vicious cycle.

Asia and Japan will continue to need the United States as the ultimate guarantor of security in the region. But middle-power cooperation has other advantages. If Japan adopts a middle-power attitude one of its main objectives will be to co-exist with China. The key to this middle-power approach is, therefore, to balance and integrate the hedging and engaging policies toward China as a coherent and shared strategy among middle powers in the region. The first step towards this goal is forming an epistemic community among Asian civil societies. To open up this new dimension of middle-power cooperation, there is no more natural partner than Japan and Australia.

Yoshihide Soeya is Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the Faculty of Law, and Director of the Institute of East Asian Studies, Keio University.

This article appeared in the most recent edition of the East Asia Forum Quarterly, ‘Coming to terms with Asia’.

Yoshihide Soeya provides a clear essay, but I feel he dismisses Japan from the beginning. Although the article is centered on the “prospects” for a Middle-Power Japan, he actually begins by suggesting it has been one since the end of WWII. This downplay of its power until the 1990’s (when the author suggests Japan begins its decent towards Middle-Power) is far from the truth; Japan’s influence and capabilities up until this point were that of a ‘Great Power’. Further, he provides no actually proof that Japan will slip to a Middle-Power Asian power in the near future.

First, to suggest that Japan has been ‘limited’ by its security alliance and article 9 is simply wrong. The Yoshida Doctrine turned what some (realist first among them) would call a weakness (pacifism) into a powerful strength. The U.S., then as it does now, pressured Japan continuously to ‘do more’ militarily. Japan, staring down the world’s democratic ‘Super Power’, said no. Its continued ability to levy its strategic importance against the United States provided it unprecedented protection and the ability to grow in such a way as to challenge the economic consensus of the time!

While it is true that post-war Japan was never sailing its navy around Asia and imposing its will like other great powers throughout history, Yoshihide himself admits Japan’s overall impact has been invaluable nonetheless. Its economic, developmental, and democratic impact in the region – including South Korea – have fundamentally changed the world order. Yoshihide – no doubt due to word limits – excludes its impact on the ADB and its vast ODA programs.

Japan’s impact on the world – economically, politically, and yes, culturally – are of Great Power status. For a moment on culture, Yoshihide suggests S. Korea may have surpassed Japan in cultural influence. To this I say that while K-Pop may be more popular in China’s dance clubs, it is pokemon that has reined supreme in Europe and the United States. Psy – if that is what the author had hinted at – has faded, too.

During its time as a ‘middle power’, as suggested by Yoshihide, Japan has contributed greatly to the redevelopment of Afghanistan, contributed to the Middle-East peace process, and championed a variety of UN missions. It has contributed to the anti-piracy missions near Somalia and expanded its own security and cyber-security systems, built a module for the ISS, and is still a technological leader.

Has the rest of East/South East Asia caught up in a variety of levels? Absolutely. China, however, will not need to worry as much about Thailand, Malaysia, or Taiwan as it will Japan when it writes its security, economic, and political white papers. Economic development does not, itself, bring political influence or power – even realist have accepted that it takes something ‘more’.

Will Japanese armies be able to march across the continent anytime soon? Absolutely not – but this does not relegate it to Middle Power status. Asia will have two Great Powers – China and Japan – although one will, admittedly, surpass the other soon enough.