Anti-minority violence perpetrated by Hindu fanatics, often with state complicity, reminds us of the precariousness of life as a minority in India. While majoritarian nationalisms (Hindutva in India and Han chauvinism in China) are dangerous threats to the mainstream multiethnic nationalisms in both the countries, their lethality is more obvious in India than in China. The Chinese system is authoritarian, but it is so for everyone. Many Han Chinese feel that the government appeases the minorities but they cannot do anything about it. In India, this feeling of perceived appeasement of minorities contributes to the success of rightwing political parties like the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

If we shift from state-majority-minority relations to the relations between the State and the ethno-nationalist movements in the periphery, again there are some apparent differences between China and India. Protests in Tibet in 2008 were quickly followed by a complete expulsion of foreign media, a crackdown, and a denunciation of the Dalai Lama and foreign forces for encouraging separatism. Ethnic violence in Xinjiang in 2009 was handled slightly differently. More foreign media were allowed (mainly because the government knew that, in contrast to Tibetan Buddhists, Westerners were unlikely to have sympathies for Uyghurs Muslims) but the attitude toward demands made by the protestors remained uncompromising. Internet is severely restricted in Tibet and Xinjiang and was in fact completely banned in the latter for many months after the protests. It has become clear that the Chinese government will not accept any outside pressure on matters it considers to be ‘internal affairs.’ Nor will it recognise as legitimate any demands made by citizens for greater participation; any change that comes, must occur from the top-down. Even a whiff of separatism and a crackdown is inevitable.

Kashmir is different, partly because the Indian system is different, but mainly because the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir is an internationally recognised dispute. Unlike Tibet or Xinjiang, where no sovereign state questions Chinese sovereignty, all international actors see Jammu and Kashmir as a disputed territory between India and Pakistan and so sovereignty is already an unsettled question.

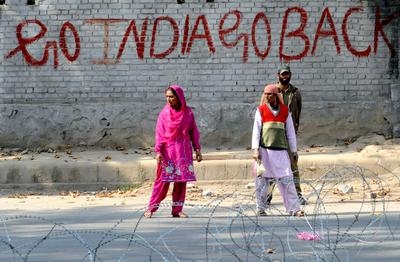

If we look at the most recent protests in Indian-controlled Kashmir, we find that more than 100 Kashmiris, mostly boys and young men, have been killed by the security forces. The Indian response to this ‘threat to sovereignty’ is different from the Chinese one. Kashmiri political leaders, including moderate as well as hard-line separatists remain very much in public, announce their protest calendars, denounce the Indian government, and the media can approach them. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and the internet has been utilised by Kashmiris to mobilise and raise awareness, even as local journalists face severe restrictions. The Indian prime minister has appealed to the youth for calm, politicians visit Jammu and Kashmir capital Srinagar for ‘fact finding’, and an eight-point plan has been put forward to solve the problem.

But, and this is a significant but, it is a mistake to over-valorise the differences between India and China. The Indian approach is no less repressive when you look at the actual experience of Kashmiris, or many other ethno-nationalist communities living in north-eastern regions of the country. The face of Indian democracy that the marginalised communities witness here is worlds apart from the celebratory tone of the overwhelmingly nationalist Indian media, as well as compliant Western commentators.

Democracy for Kashmiris and many in the North East has meant corrupt and compliant local elite propped up by the Centre through fraudulent elections; everyday humiliation and reminders that mainstream India does not trust them; the overwhelming presence of the security forces, protected by special laws; the onslaught of Indian propaganda, often with active complicity of broadcast media, to misrepresent all demands made by the ethno-nationalist activists as illegitimate and as stemming from extremism.

If one goes behind the fog of propaganda and misperceptions and closely studies Chinese and Indian government policies and practices in the peripheral regions, they’d see that the rising Asian powers have more in common. When it comes to dealing with ethno-nationalist communities questioning the dominant nationalist narratives, a fight against ‘separatism’ and ‘splittism’ overrides any concern for rights enshrined in the states’ own constitutions. In this sense, both China and India are, what I term, ‘postcolonial informal empires.’ While claiming to be anti-imperialist, both countries seek to consolidate and discipline their borderlands and reduce the people living there into culturally different but politically subservient subjects.

Dr Dibyesh Anand is an Associate Professor in International Relations at London’s University of Westminster. His research interests include majority-minority relations in China and India, Tibet, and China-India border dispute.