Opaque state–business relations have always existed and evolved along with economic and political change in India.

India’s development after independence from colonial rule has always involved partnerships between the state and private businesses. The specific division of roles and responsibilities among them in the formal policy structure has changed from time to time. But the state’s role has never been either minimalist, or of a kind that would undermine the substantial influence of mainly family-controlled businesses in the economy.

A strong tendency towards a ‘partnership’ approach consisting of personal relationships between individual business groups and state decision-makers has instead been a persistent feature of India’s corporate scene. The ability to influence the decision-making through which policy is executed has been an important factor in business success.

It is not that the Indian state is a completely captive agent of a select few business families. Competition and rivalry between businesses has never been completely absent — but the economy has always included an important non-market component.

A pervasive tendency towards divisions within family-controlled groups, sometimes quite acrimonious, has also been a feature of business in India. If India’s state–business relationship is distinctive in any sense versus peers overseas, it lies in the in the state’s weakened capacity to discipline private capital.

Initial attempts after independence at economic planning and at placing the public sector at the ‘commanding heights of the economy’ relied on public investment in designated activities rather than nationalisation of private enterprises. The Indian government used licensing to apportion investment opportunities among private enterprises. The nationalisation of some strategic sectors in the late 1960s and 1970s — like banking, general insurance, coal mining and oil — and government takeovers of ailing private companies happened against a backdrop of the collapse of public and private investment and increasing political unrest.

Although most of the manufacturing sector remained in private hands, in the 1980s public sector institutions financed an import-liberalisation based expansion of private corporate investment.

Government-appointed inquiry commissions highlighted that a few favoured large business groups were typically disproportionately awarded opportunities until the mid-1960s. But the period that followed saw an effective collapse of planning and the onset of what was described as the era of ‘briefcase politics’, where the state–business relationship became more transactional in nature.

While the entire period before the 1991 liberalisation is often described as the ‘license-permit raj’, it was not oppressive for Indian big business. In the process of trying to play the regulatory regime to their own advantage, business groups were instead active agents in derailing any real state-mediated coordination of the economy. Businesses undermined any efforts aimed at improving tax mobilisation and reducing technological dependence.

After 1991, several activities where the public sector had acquired dominance — banking and insurance, mining, telecommunications and broadcasting, airlines, infrastructure and so on — were opened up to private enterprises, while some public enterprises were privatised. Many of these sectors have played an important role in Indian growth and in the country’s unprecedented corporate expansion.

But the impossibility of competitive markets in many of the sectors meant that the state remained on the scene as a regulator that had to set and enforce the rules of the game.

Increased foreign competition has also reinforced the need for state support. Fiscal constraints increased the dependence of the state on private capital to drive the economy. Public sector financial institutions even financed private investment in infrastructure, traditionally a sphere of public investment, resulting in huge defaults and a number of corporate scandals in recent years.

Liberalisation did not eliminate the importance of state backing for Indian big business. It only increased the leverage of big capital over the state. The extreme marginalisation of some social classes are one direct result of this.

On the one hand, this relationship between the state and businesses created the conditions for corruption and cronyism. On the other hand, it generated a tendency for the Indian state to prioritise coercive approaches over developmental ones to keep social unrest in check, which was been reinforced by a loss of momentum in private investment-led growth during the 2010s.

The creation of a completely non-transparent system of political funding through electoral bonds and a clear trend of politicisation of the state’s law enforcement agencies and processes have been part of the weakening of India’s democracy.

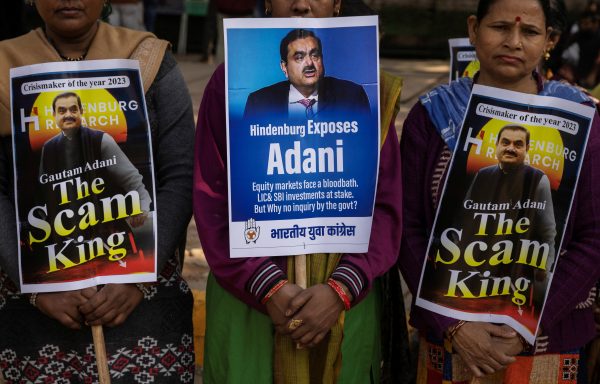

As a result, it may be the case that the Adani scandal alleged by Hindenburg did not involve specifically asking for favours, making direct payoffs or giving any specific political directions.

The commonly held belief about Adani’s closeness with the government may have been sufficient to ensure that the risk-benefit calculus facing other market players, including public sector financial institutions and regulatory bodies, all incentivised cooperating with Adani. A similar calculus may have also guaranteed the silence of India’s mainstream media until Hindenburg broke the story.

Surajit Mazumdar is Professor in the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University.